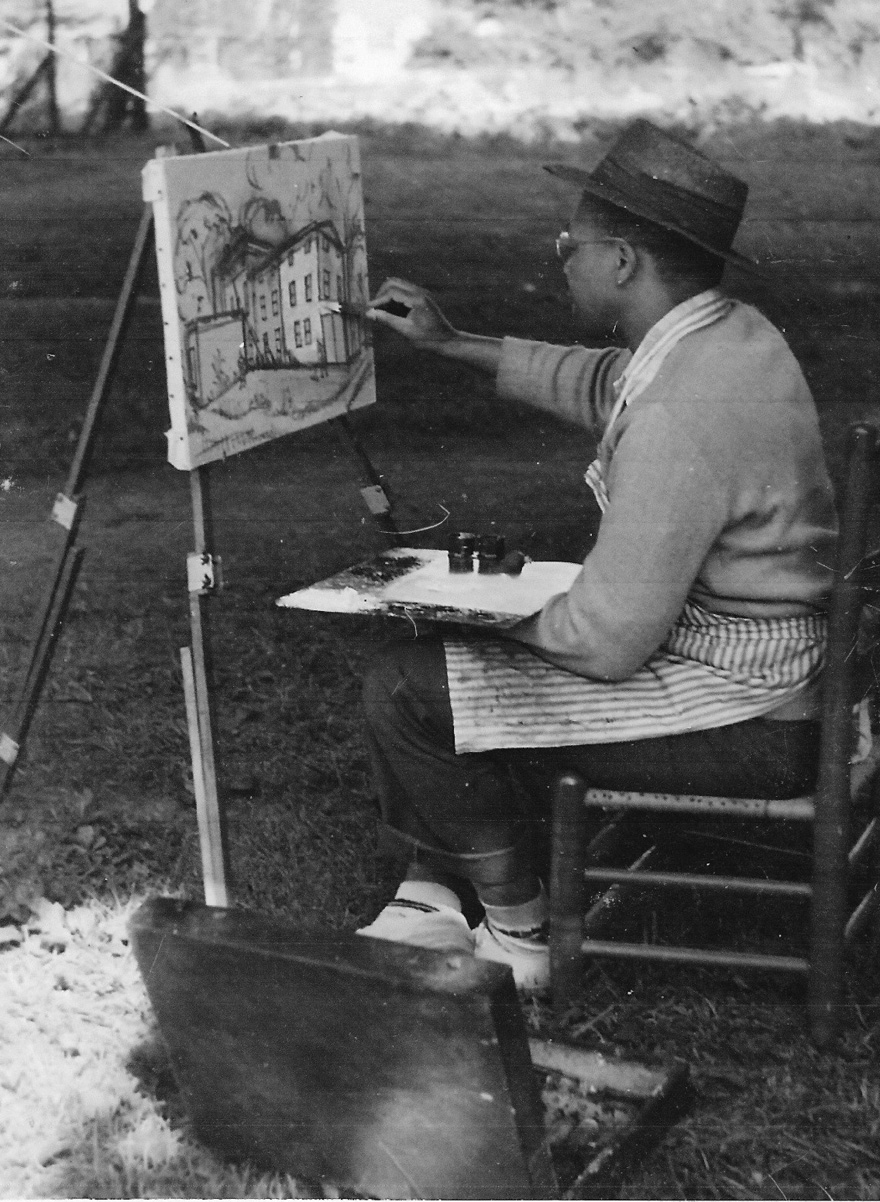

Claude Clark was an easel painter. He used European tools and methods of work. Clark did a variety of work ranging from figures, flower studies, landscapes, boat marine life and nonobjective abstract. Clark was a master of light and color. He has been listed in numerous art directories and books. Clark's work can be found at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C., de Young Museum in San Francisco, plus numerous other major art museums and collections throughout the country.

Please take a look at the Gallery of 200+ paintings available for exhibit.

Artist StatementMade by Claude Clark in 1989 - As a child in the churches, the schools and the community, I dreamed of a destiny. My search became a single purpose for the dignity of Black Americans instead of attempting to solve the concerns of all humanity. Early on, I was convinced a creative spirit must soar beyond compartments of religion and politics. It was through the roots of African Art that I learned of the creative source of most Western art. As I stood near the Nile at Cairo and looked toward the Mediterranean in awe, I envisioned how the Greeks, Persians, Romans, etc., had sailed up the Nile, taking away the fine arts, sciences, history and other disciplines. There were records on paper, on stone, on walls in the temples that rivaled anything produced later in the Renaissance....

Over the years, I have painted representative and figurative subjects. About thirty years ago, I was introduced to Non-Objective Expressionism. I didn't attempt abstract art in the 1930s, nor did I try during my years at the Barnes Foundation. Dr. Barnes not only has the world's finest collection of Modern Art, but presents the theory in his book, "The Art of Painting," that the format of the Modern Masters was the same as that of old Western Masters. For instance, the contemporary artist presents a simple design, while the old Master presented the same format, but built in the detailed subject matter. I believe that the African creative artists gave the format to the Western world and they are masters of design (especially Egyptians). I feel that I understand contemporary directions; and I relax for a while, to have fun such as with inventive avant-garde. I have learned much that I have applied to my craft, and I feel that I have become a more flexible creative spirit.

Top of Page

by Eloise Johnson, PhD.

African American Art History

"As a child in the churches, the schools and the community, I dreamed of a destiny. My search became a single purpose for the dignity of Black people..."

Claude Clark was born November 11, 1915 on a tenant farm in rural Rockingham, Georgia. A painter, printmaker and educator, his work characterizes the African American experience. Clark's subject matter is woven from the threaded Diaspora of African American culture. It includes dance scenes, street urchins, landscapes and still-lifes executed primarily with a palette knife. His bold, assured strokes of the paint illuminate the exaggerated movement of Black dance and the luscious texture of foliage and fruit.

In early August 1923, Clark's parents became part of that great exodus of blacks leaving the south for a better life during the Great Migration. They traveled to Philadelphia where Clark attended a predominantly white school. Clark experienced overt racism while attending high school, but did not allow it to deter him from his dream of becoming a poet or an artist.

From 1935-1939, Clark studied at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art. While there, he again experienced racism from some of his instructors. However, others like Frank Copeland and Earl Horter were supportive. Henry Pitz influenced his figurative work and Franklin Watkins was inspirational in showing him the freedom inherent in painting. By the third year, Clark won the painting prize and Watkins purchased some of his works. While studying at the school, Clark's teachers introduced him to the technique of Van Gogh in the handling of the still life. The execution of this style formed the basis of his approach to drawing and painting. In his composition, Van Gogh and Cezanne's influence can be felt in the thick creamy texture and loosely applied paint. The palette knife became his tool of choice and Clark's deft handling of it has been his signature trademark.

Clark recalled: "I dared to paint in the drawing classes instead of using charcoal. The students at that school were quite amazed ... I wanted to get as much painting as possible. But doing this time there was a suspicion of modernist techniques as opposed to the traditional methods of making art. "I heard the other students called me 'a filthy modernist,' because I was applying the paint with a palette knife."

His work was sometimes labeled "neo-primitive" or "neo-Baroque." It is important to note that there would be a backlash against this type of art during the next decade in which abstract art would be considered modem while realistic painting would be condemned as non-progressive.

Wilhelm DeKooning would be vehemently scandalized a couple years later for painting realistic subject matter, while the use of the palette knife would become the norm in artistic circles. Clark applied to the distinguished Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania in 1938, but missed his appointment. He reapplied and was accepted in 1939.

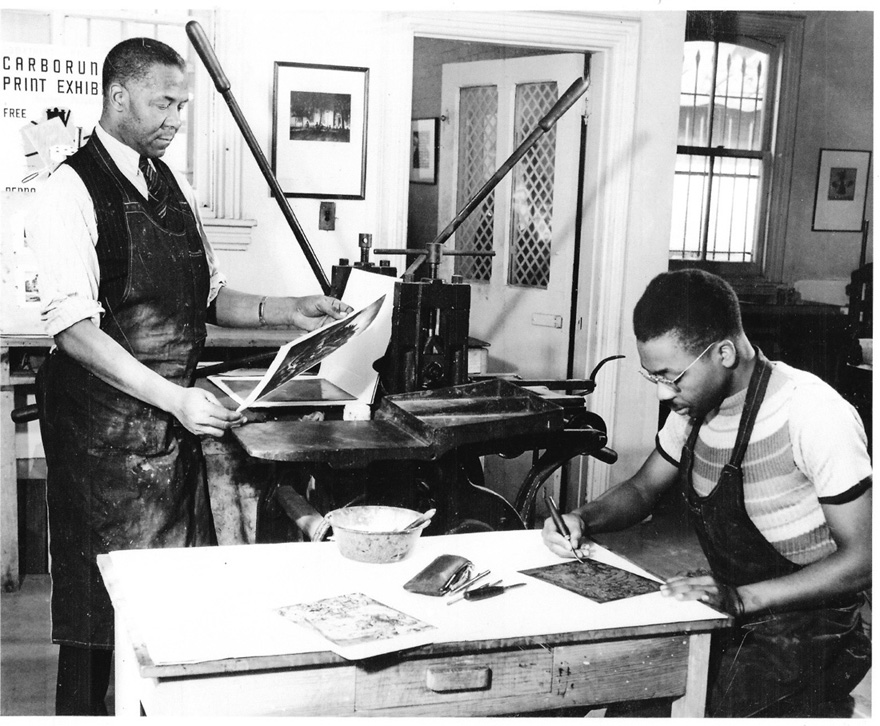

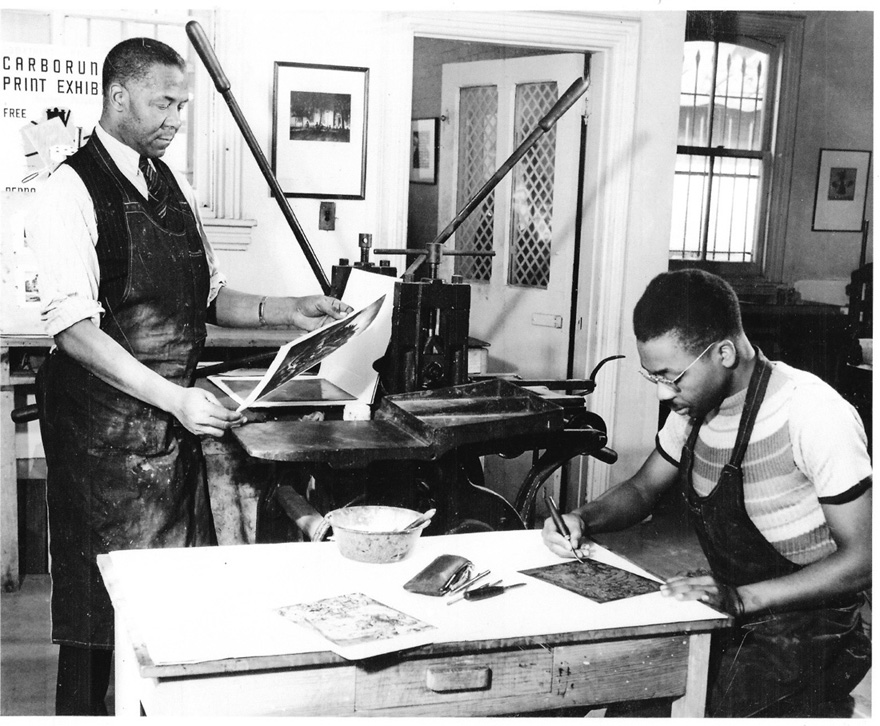

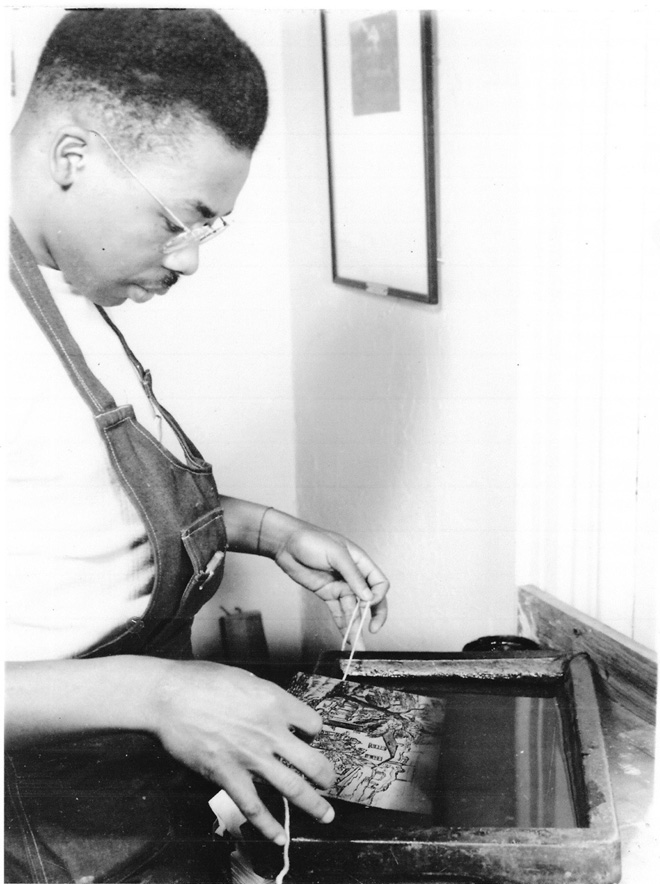

In 1939, during the Great Depression, Clark was desperately searching for a job. He heard that the Artist's Union would provide jobs through the Federal Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). He contacted the union and they found him a job at the WPA. Clark worked with the WPA from 1939-1942. The artist's credo about art was that it should benefit the common man. This related to the ideology of the Mexican muralist who was committed to an art for the people. Thus, he began to work in a medium that would reach the masses. He joined the graphic arts shop where he worked and shared a studio with Raymond Steth. Here, he became acquainted with Dox Thrash. During this period Thrash discovered a new carbonundum printing technique while employed there. Clark along with others at the shop would experiment with new techniques; including a color etching process.

In 1941 Clark met Effie Mary Lockhart from California, the daughter of an AME minister. They married in June 1943. Clark then obtained jobs in Philadelphia after his tenure with the WPA. His work has appeared in numerous shows including the Albany (NY) Institute of History and Art's 1945 presentation "The Negro Comes of Age." His first solo show was at the Artist's Gallery of Philip Ragan Association in Philadelphia, 1944. Also, he was the first black artist featured by Dorothy Grafly.

His first New York show was at the Bonestell Gallery in 1945, followed by one at the Michael Freilich's Roko Gallery 1946-1947. With the purchase of "Cutting Pattern" from his 1944 Artist Gallery show, by Albert Barnes, Clark became the second living African American artist, after Horace Pippin, to have his work displayed by the Barnes Foundation.

Top of Page

Clark's WPA work shows his affinity for social realism. An example of this is seen in Guttersnipe, 1942, a recent purchase by Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. It shows a cocky street-kid smoking a cigarette. The subject matter examines issues of race and identity that continues to haunt African Americans. Other early works from the 1940's reveal a celebratory spirit in such common themes as Jam Session, 1943. These dance scenes are an exploration of African Americans partaking of the life in the urban landscapes.

In contrast, Vase, 1946, a still life of vibrant colors, reminds us of the sheer "Market Place (Virgin Isles), 1946", Oil on Canvas 24"x 20” pleasure that a vase of flowers can give. Its sensuous textures emphasized by the palette knife make the flowers pulsate with energy. The color harmonies within the composition add a subtle touch to the luscious paint textures. In the 1950s and 1960s Clark's themes changed due to his travels abroad to Africa and the Caribbean. In Street Scene, 1954, Clark examines the sense of loneliness and abandonment that prevails in urban areas. The abandoned building is reminiscent of William H. Johnson's Jacobia Hotel, 1930, with its expressive character and movement. The atmosphere also relates the sense of alienation and abandonment in the work of Edward Hopper.

As early as the 1940's, Art News recognized his rare artistic ability: "Claude Clark (Roko: to March 31, 1947) ... presents ... an art in which strong feelings are translated into paint. Forceful army scenes, figure studies...and powerful landscapes reveal Clark's concern with human and psychological values. Brilliant color harmonies and a moving sense of design contribute to their achievement. The flower paintings show his feeling for color at its purest…”

In the 1940s, Clark became interested in working in a black college. After writing many letters of employment, he received offers from two: Jackson State University in Mississippi and Talladega College in Alabama. Jackson State offered the higher salary, but he chose Talladega because it provided housing, which he desperately needed for his family. Originally, he went to Talladega in 1948 to do a workshop. However, many of his students, who were war veterans requested art training. Due to an increased student demand, he established a full time art department. Determined to educate his students in their own cultural history, Clark exposed his students to African and African American art.

In 1950, he won a Carnegie Fellowship, which allowed him to spend the summer in the Caribbean, mainly Puerto Rico, painting still lifes and landscapes. In 1955, at the end of the spring term., Clark left Talladega. Without another employment engagement, he moved with his family to California. More importantly, he was urged to do so by Mrs. Clark; she recalled, "I could see that we could not send our two kids to college if he stayed in Talladega. I couldn't find a job in Talladega." Mrs. Clark had a Master's of Philosophy degree from Howard University and had studied under Alain Locke. She could not obtain a job at the college nor in the public school system. The move became a career and economic necessity for both of them. Subsequently, in the fall of 1955, he registered at Sacramento State University and received his undergraduate degree in 1958. He moved to Oakland California in 1959 and attended the University of California at Berkeley. Majoring in painting with a minor in social studies, he obtained his Masters of Arts degree in 1962. Meanwhile, Mrs. Clark managed to obtain two additional degrees at the Pacific School of Religion at Berkley. One was a Master's of Theology and the other, a Master's in Religious Education.

During this period Clark's color palette lightened and his technique became freer with such works as Homestretch, 1961 and Ascending 1961. Market Place (Virgin Isles), 1961 also shows the lighter color palette and his continued interest in abstraction.

Clark found employment at Oakland's Merritt College in 1968 and stayed until his retirement in 1981. In 1969 Clark wrote "A Black Art Perspective: A Black Teacher's Guide to a Black Visual Arts Curriculum." Clark has exhibited with many famous African American artists such as Henry O. Tanner, Romare Bearden, Richmond Barthe, William H. Johnson, Aaron Douglas, Charles White, Ellis Wilson and Jacob Lawrence. Additional exhibits have been held in Paris, Puerto Rico, Mexico and throughout the United States. In addition, to private collections, his works can be found in public and museum collections, including the Smithsonian Institute, National Gallery of Art, Talladega College, Fisk University, Atlanta University, Hampton University, DuSable Museum, Chicago; Oakland Museum, Oakland; Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, San Francisco; the Library of Congress and Bill Cosby purchased a painting entitled My Church as a gift to Reverend Jesse Jackson.

Claude Clark died April 21, 2001 leaving behind a void in the African American art community. Mrs. Clark talked about his sense of humanity in his art and life. "I felt that he was a very generous man with his art and his knowledge. He didn't have any working hours because he was always working...sometimes to his own detriment. I consider him one of America's greatest colorist. He ground his own paint, you know..." Clark's brilliant work has secured him a position within the history of art.

An innovator, an educator, and an icon of the first caliber he has woven a tapestry that is rich with the extraordinary design of our lives. Within its pattern, we danced the jitterbug, we laughed, we cried, we played and listened to jazz music, we remembered the southern folk tradition. We knew that we were connected to others in Africa and the Caribbean; we sensed it in his wonderful paintings. A transplanted Southerner living in California, he maintained his "southern ethos" in the midst of urban life.

Top of Page

Personal History

Born: November 11, 1915 in Rockingham, GA

Education

Philadelphia Museum School of Art, Certificate, 1935-39

Studies at Barnes Foundation, Merion, PA, Fellowship, 1939-44

Sacramento State University, B.A.1958

University of California, Berkeley, CA, M.A., 1962

Career

Works Progress Administration (WPA), Printer, 1939-42

Philadelphia Public Schools, Philadelphia, PA, Instructor, 1945-48

Talladega College, Talladega, AL, Assistant Professor of Art, 1948-55

Alameda County Juvenile Facility, Oakland, CA, Art Instructor, 1958-67

Merritt College, Oakland, CA, Art Instructor, 1968-81

Author

“Black Art Perspective: A Black Teacher's Guide of a Black Visual Art Curriculum”, Merritt College Press, Oakland, CA 1970

Awards

Silver Medal, St. Nicholas League, 1933

Barnes Foundation Fellowship, 1942

Carnegie Fellowship, 1950

Commission

“Freedom Morning” Oil on Canvass, 1944, commissioned by the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra

Top of Page

Selected Group Exhibitions

Selected Solo Exhibitions